That’s what this film is really about, I think. Not just the falcons—though they’re magnificent—but the people who’ve decided they’re worth saving.

Ulaanbaatar, 17 July 2025

My hands are still shaking a little as I write this. Not from the cold—though it gets quite cold here even in July—but from everything that’s happened these past five days at Bayan. Kiran and I are back in Ulaanbaatar now, and I keep catching myself staring out the window, half-expecting to see those endless steppes rolling past.

I’m not sure I have the words for what we experienced out there.

Every morning started the same way: my phone buzzing at 4 a.m., stumbling around in the dark trying not to wake Kiran, then that first sip of Kenyan coffee (I always carry with me) while the world was still completely silent. Buddy—this raven (photo below) who decided we were interesting enough to follow around—would already be awake, making these ridiculous chuckling sounds that somehow became the soundtrack to our mornings. Then the sun would start to creep up, and wow, the way the light hits those steppes… I must have taken fifty photos of the same sunrise and somehow, they all look different.

But none of that prepared me for Simon.

That’s what we called him—X20 on the research ring, but he needed a real name. This recently fledged saker falcon who, for reasons I still don’t understand, decided we were okay. Maybe it was because we sat so still for so long, or maybe he was just curious about these two idiots with cameras. But there was this moment—I was cross-legged on the ground, maybe a meter away from him, and he just… looked at me. Not the quick, darting glances birds usually give you, but this steady, almost thoughtful stare.

I realized I’d been holding my breath.

Kiran caught it on camera, thank goodness, because otherwise I’d think I dreamed it. This wild creature, this perfect predator, just sitting there with us like we were part of his world. He had this little limp—probably from his tracking ring, or maybe he was just born that way—but when he took off, he flew like poetry. Like someone had written grace into the sky and he was reading it aloud.

I keep thinking about that limp. How he didn’t let it slow him down, didn’t let it define him. There’s something in that, isn’t there? About making do with what you have, about finding your own way to soar.

The weather was fantastic on most days but then there were those days where it was absolutely terrible —rain, heavy clouds, the kind of grey that makes you forget what blue looks like. We had this brilliant idea to drag a dead goat around to attract vultures. (Note to self: next time, bring nose plugs.) Only one cinereous vulture showed up, probably wondering what these humans were doing with their rotting goat.

Speaking of scavengers, this corsac fox (we named him Charlie) basically adopted our camp. Cheeky little guy stole a dozen of our eggs and buried them all over the place like some kind of furry pirate. We’d find them days later, perfectly buried in neat little holes. I couldn’t even be mad—watching him work was like watching a masterclass in determination.

One evening, I got homesick for proper food and decided to cook. Indian curry, right there on the steppes—corn, peas, potatoes, some beans. I’d carried some Indian spices from Abu Dhabi. Made karak chai in a beat-up pot while the sky turned purple and orange above us. Kiran said it tasted like home, which made me ridiculously happy. Sometimes the smallest things anchor you.

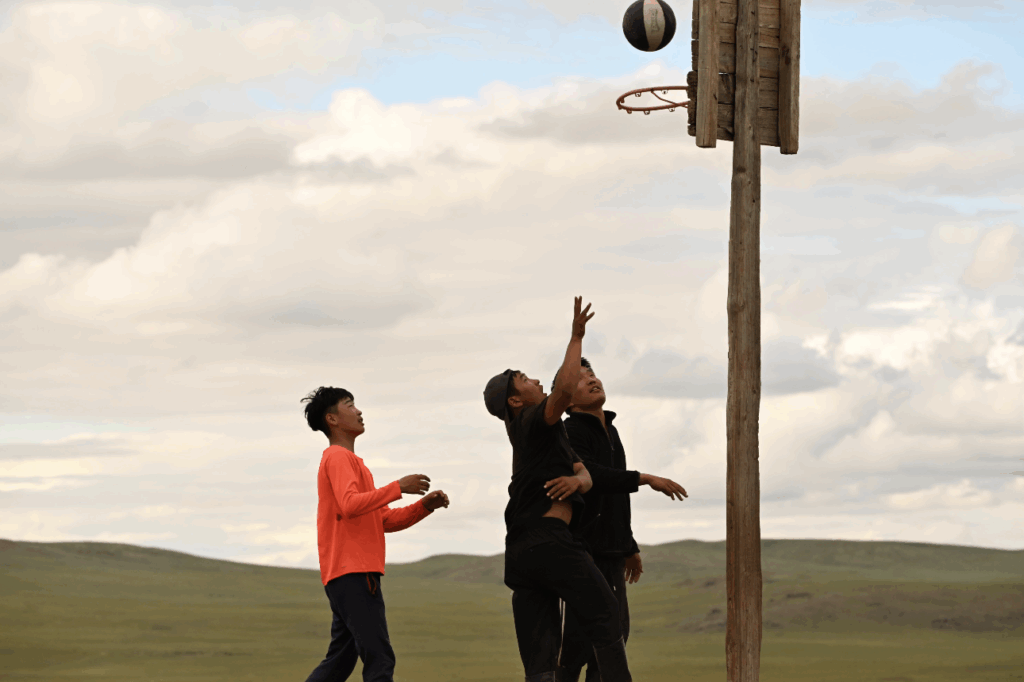

The filming went better than I hoped. We got this incredible shot of a saker falcon nest while kids played basketball in the background—this perfect collision of wild and human that somehow just worked. It’s exactly what Sara and her team at Saraana Nature Conservation Foundation are trying to protect.

Sara. Wow, what a woman. She drove straight from the hospital to meet us—her week-old baby had an ear infection, she hadn’t slept in days, and she still showed up to talk about falcon conservation. With baby in next room, Sara explained how they’ve put up 80 artificial nests around Gun Galot Nature Reserve, how they’re working with herding families to become guardians instead of just observers. These families are proud of their falcons now, Sara said. They know the birds keep the rodents away, protect their livestock, bring good luck. It’s working because it makes sense to everyone involved.

Back in the city, we interviewed Huyagaa from the Mongolian Bird Conservation Center. He founded the organization in 2015, has been doing this work for years, and you can see it in his eyes—the exhaustion, yes, but also this unshakeable belief that it matters. He has built an incredible and committed team around him. The MBCC has been our partner through the Mohamed bin Zayed Raptor Conservation Fund, and they’ve done everything from building nests to tracking birds to convincing communities that raptors are worth protecting.

But it’s people like Aggii who gives me the most hope. This young student who’s about to start his PhD, who picked us up at dawn without complaint, who spent all day tracking falcons and never once looked tired. There’s something in his eyes—this spark that says he sees the future and wants to be part of building it. He’s the kind of person who’ll still be doing this work in twenty years, probably training the next generation of conservation scientists.

That’s what this film is really about, I think. Not just the falcons—though they’re magnificent—but the people who’ve decided they’re worth saving. The herders who’ve gone from seeing raptors as pests to seeing them as partners. The scientists who wake up at 4 a.m. to count nests and track migrations. The kids playing basketball while falcons nest nearby, growing up in a world where both can coexist.

We’re calling it “Saker Skies: The Legacy of X26,” but honestly, it’s about legacy everywhere. Between wild and human, between tradition and progress, between individual need and collective good. It’s about trust—the kind Simon showed us when he let us into his world, the kind Sara’s team is building with herding communities, the kind that makes conservation actually work.

I’m writing this at 2 a.m., exhausted, caffeinated and emotional and probably not making complete sense. But I needed to get it down while it was still fresh, while I could still feel the weight of that moment with Simon, still taste the karak chai under that enormous sky.

We’re not just making a documentary. We’re documenting something precious and fragile and absolutely worth fighting for. And as long as there are people like Aggie ready to carry this work forward, I think we might actually win.

The skies above Mongolia are still sacred. We just need to remember why that matters.

Leave a reply